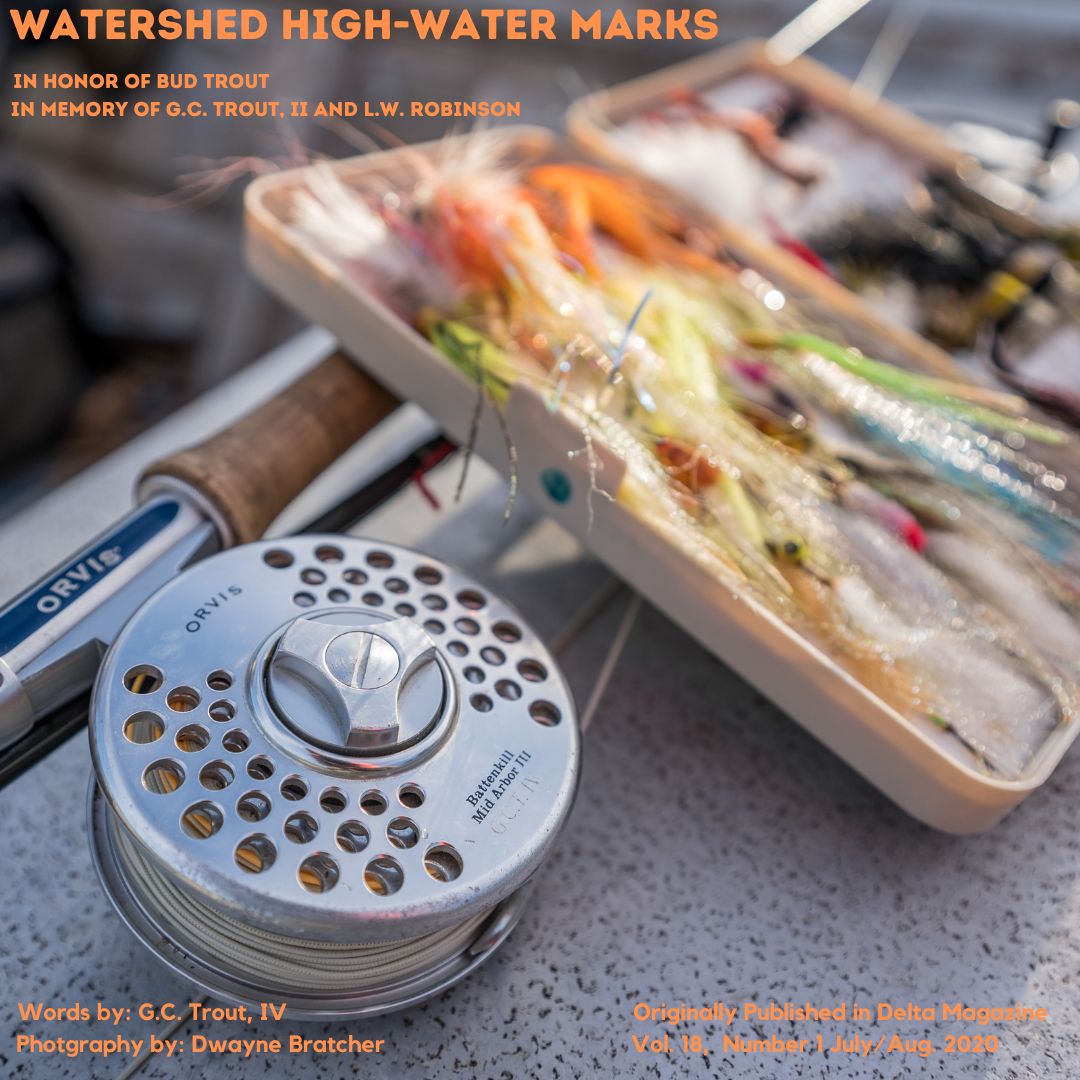

Watershed High-Water Marks

Memory believes before knowing remembers. Believes longer than recollects, longer than knowing even wonders.

–William Faulkner

Among myriad methods for landing largemouth bass, the non-pareils of fly fishing persist. The cast. The strike. The fight. There are few endeavors in this life offering greater satisfaction than netting a warm-water carnivore of, say, five pounds on a flimsy five-weight fly rod. The strike is a shock. A thrill. It’s a fight to which you are barely equal… a joy unsurpassed in success.

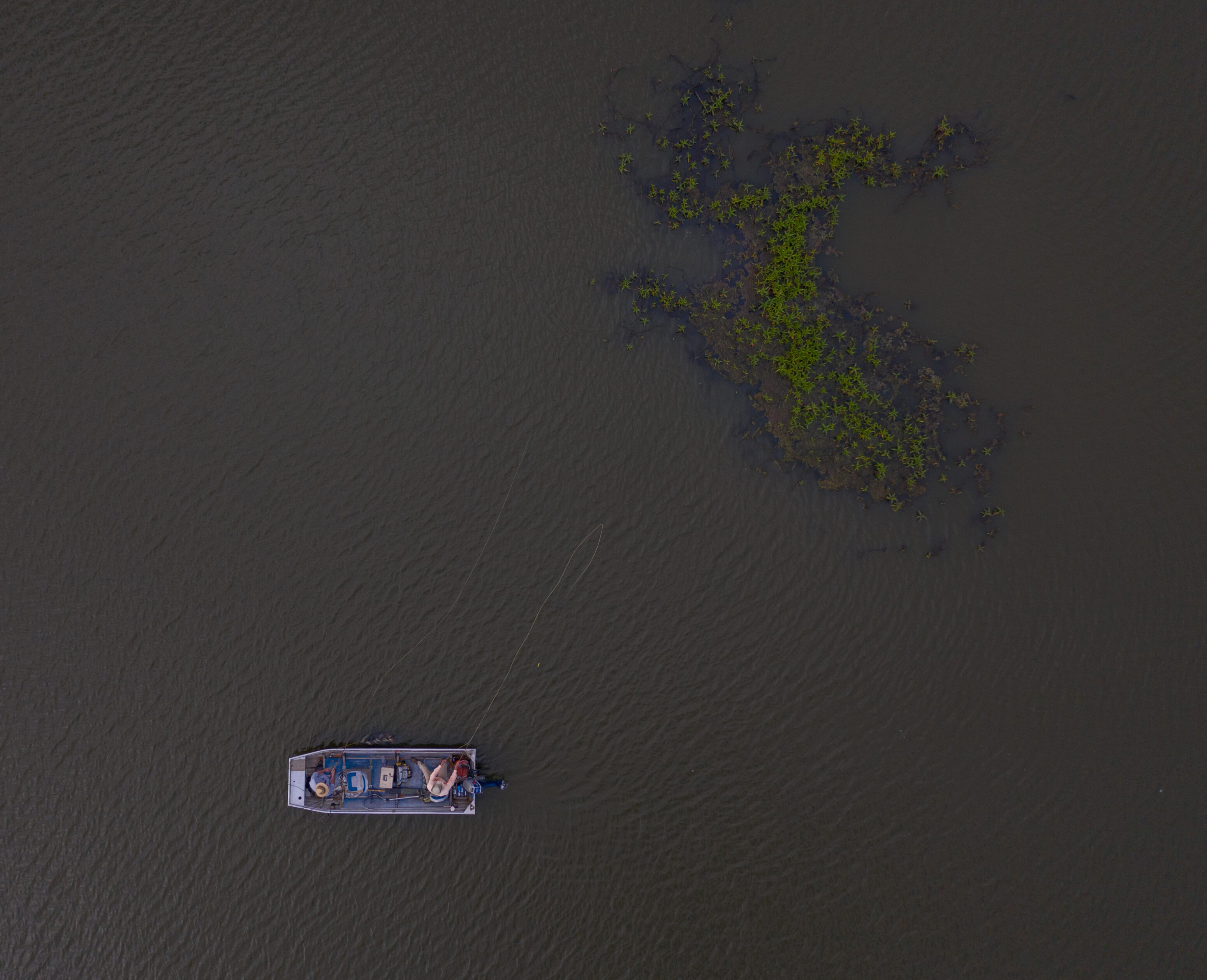

I’ve been fishing the watershed lakes in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi since I was a child. From then until now, I’ve haunted the waters of the Hubbard-Murphee Drainage District. Lakes carrying such names as Ryals-Wrenn’s, Lowery’s, and Poor House.

Poor House, where I have vivid memories of fishing as a child, with my brother on one half of the front boat seat, while I sat on the other as our father motored us across lily-strewn waters towards a fishless day. We were alone, aside from a local coach, who showed us a tremendous stringer-full of bass and crappie. He was rumored to be mostly Choctaw. I recall the way the light worked on his red and ruddy skin, cerise in the boozy and florid light of sundown. An hour later we returned home with nothing, save the memory of a happy day spent with my father and my brother.

In these lakes live leviathans, though. Lately, I know of a 12.5 and a 13.5 lb. bass caught out of them; and more 7-9 lb. bass than we can record. But, at some point, the numbers become superfluous. Fishing is about catching fish, yes. But it’s mostly about unwinding, spending time with loved ones, problem solving. As Mississippi writer Barry Hannah once noted, “there’s nothing more contemplative than a body of water.”

Located high in the Loess Bluffs that skirt its eastern edge, watershed lakes provide a vital service to the Delta. There are possibly hundreds of these lakes throughout 30 or so such districts. Hubbard-Murphee was organized in the late 1950s by my grandfather, G.C. Trout, and two other landowners, A.A. Mabus and N.C. Shook, who saw the need for more localized control of the flooding that plagued their farms. The primary result is thousands of acres of land with improved drainage and reduced flooding. This led to farmable and inhabitable land where it didn’t previously exist.

The greatest collateral benefit is they tend to be terrifyingly fine fishing lakes. The fact that my paternal grandfather, who passed away when I was a baby, was not only a founder and the first president of this drainage district, but also enough of a fly fisherman to own a nice split-cane bamboo fly rod my father allows me to use occasionally makes the connection all the more special.

I learned to fish from my father, Bud Trout, and my maternal grandfather, L.W. Robinson, a man who told me much in the 16 years I knew him. Three things come to mind regarding who he was and his philosophy.

Once, I asked him what he was… where his people came from. He replied, “I’m Dutch, Irish and Devil, Son.” And left it at that.

Another time, as we drove by a golf course, he half-snorted/half-chuckled, “Golf…that’s what people do when they get too old to fish. I want to live a good long life, but I don’t want to live so long I have to take up golf!”

Later in his life, when I was 15, he told me, “You should get up every morning and watch the sun rise. No two are the same. Every one is beautiful. You never know which one will be the start of your last day on earth. Two years ago the doctors gave me six months to live…” He trailed off, staring into the sun. I like to think he was ruminating on a perfect day on a nearby lake with his wife, Mary Agnes, hauling in crappie.

One of my earliest memories fishing is with him and my brother, Daniel, in a lake near Teasdale. I remember catching two catfish before Grandaddy baited his hook. I was certain I was going to out-fish him. But I didn’t then, nor did I ever.

I don’t believe Grandaddy knew how to fly fish. But, he taught me the finer nuances of catching crappie, bream, and catfish with livers, worms, and crickets. This angling craft is indispensible. In some ways it’s like learning scales in music, or perhaps Heart and Soul compared to fly fishing’s Fifth Symphony. Or, maybe, more simply, if you’re looking to put fish in a skillet, Grandaddy’s method works every time.

My parents gave me a 5/6 weight L.L. Bean fly rod for my 16th birthday, about two weeks before Grandaddy passed away. It came with a reel, line, and small piece of scarlet yarn tied to the end of the leader. My heart flickered. I looked at it all with the curiosity and excitement of an ancient man first beholding a red and blazing flame.

Later that day, under the cherry, oak, and sweet gum trees that punctuated our backyard, my father taught me to fly cast. He showed me the basics. Then, as is his fashion, left me to fail again and fail better every time I cast that yarn at a certain sweet gum leaf some 20 ft. away. I was antsy and aggravated. Ready to tie on a fly and go fishing, he simply said, “No. You’re not ready.” And, that was my first lesson.

Fly fishing, if anything, encourages the long labor of learning to patient the mind. Practice, work, discipline, skill, art. Yes, before anything artistic occurs, there are countless hours spent in practice. These are the steps to becoming proficient at fly fishing. Well those cover the technical requirements, anyway. One must also develop a body of knowledge that includes learning what fish live where, what they are eating at any given time, how to read water and weather patterns, proper line weight, appropriate tackle, etc…

Norman MacLean, in A River Runs Through It, says his father, Rev. MacLean insisted that in a perfect world, “No one who did not know how to fish would be allowed to disgrace a fish by catching him.” He also notes, at length, that fly fishing is an art, and that “art does not come easy.” It’s fairly impossible to try it, want to excel at it, yet not realize these things are true. It is not the simple task of hooking a worm and tossing it into likely water. Fly fishing both demands and allows the body to come into harmony with your thoughts, desires, and the world around you as you work towards one singular purpose: to fool a fish.

Sounds silly, but it isn’t.

It doesn’t take too much of a romantic to see the art in such an ecosystem. A watershed lake thrums with biodiversity: snakes, frogs, insects, fish, humans. Each connected to the other in a Divine economy of violence and peace— of song and noise and quiet. Blustery wind. Perfect stillness. It sings. It sways. It thumps. Almost as though God is wrestling with what He’s created. In the center, is a man wrestling a big bass, and his own conscience, regarding its fate. He wants to land it. He wants to show it off. A part of him convinces another part of him he actually wants to eat it. Latent pride, justified by taste, hardly. Crappie are, of course, another matter.

These lakes are Holy fonts, writ large. Stoups of water where a thousand kelsons of creation are evident every second. They are a microcosm of God’s will. On display, ample opportunity to exercise His greatest hope: mercy. We see our own place in it, replete with choices we must also make. The Creator’s imagination beheld a perfect context: water, a hook, a line, hope… Here, I’m reminded, every moment, it is up to each of us to decide if we will prove Him correct.

Work. Practice. Discipline. Skill. Art. Also mercy, employed towards its highest purpose. This is not only the way to become a fly fisherman, at some point, it becomes the place you occupy as one.

And yet, for years I suffered from clumsiness. While my father fished, I untied knots, dislodged hooks, or fumbled around with gear while trying to tell a story. From time to time Daddy would say, “Hold on, Son. I need to catch this fish.” Inevitably there would be one headed to the net.

Whenever he hooked one that splashed around the surface in protest, he would throw his head back and yell in pure joy, “SPEAK!” The noise of the fight would persist until he brought it hand-more often than not towards a show of tender clemency, released back into the water.

They say a human is about 60 percent water, which seems like a lot. Some evolutionary biologists believe life itself emanates from water. Verily, man’s earliest ground-bound predecessors crawled out of the ooze of a primordial swamp in some amphibious form, before spending the next 350 million years developing into the beautiful, fumbling, imperfect, hopeful creatures we are today.

Ever seen a bass hit a frog pattern on a fly line? It’s violent. Archaic. Primal.

Perhaps the joy we feel catching fish, that innate urge we have to pursue them, emanates from a genetically-encoded, primigenial revenge mechanism in return for our primeval ancestors being fish-food…

Ah, but our fascination with fishing isn’t confined to evolutionary science. In the Bible, Christ Himself is a master angler, as were seven of the apostles, whom he enjoined, “Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.”

Among the first to answer His call is James, who teaches us that action is where thought marries belief, and redemption is born.

Though Rev. MacLean insists that James’s brother, John, is the “favorite and a dry-fly fisherman,” I’m reminded, a la Ecclesiastes ch. 1, vs. 2, the reference to the beloved disciple occurs nowhere except in the Book of John itself.

For an angler taking an angler’s advice, I say James, writing about love-in-action, had it in the net. As did Grandaddy, who loved a big smile and had a big laugh whenever the opportunity for a good laugh presented itself. And, a fish to drop in the grease, whenever one felt wanton enough to strike.

As does my father, whom I see in a still-frame of animated exuberance when playing a good fish, like the image of Christ ambling across the water’s surface: suspended, unsinkable. I think, also, of his father’s old split-cane bamboo rod, and the times he must have had with it. I am grateful for him and Mr. Mabus and Mr. Shook for wanting to improve their land, thus building these lakes.

At times, casting flies here late in the evening, after the whirling aubaude of tanager, frog croak, and grosbeak, when all movement ceases, a high breeze sighs across rippling water and these three I recall:

The moments-

the lessons-

these men.

Whatever else has been lost, here, I am at peace.