Learning to Dress for the Occasion

A large part of a rural boy’s young life—I mean life before any degree of freedom, before driver’s licenses and school dances, Boy Scout trips, or even afternoons spent in the lull of summer’s heat floating alone on farm ponds with a hook in the water and a hope-filled heart— is spent watching their father. That is, we try to imitate them, looking on as they act out their passions, examining with curiosity, and sometimes fear, the fury with which they undertake their life’s endeavors, their livelihoods.

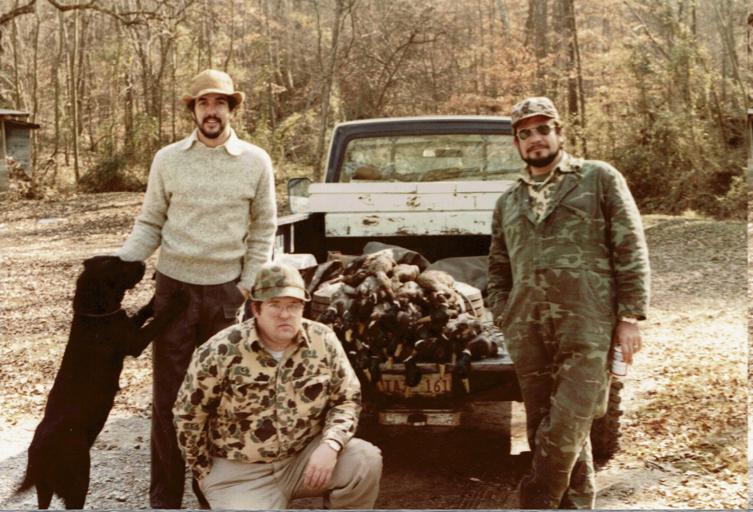

My father, now retired, was a cotton farmer, a pool shark, a poker player of the highest order. He remains a trumpet player, a lover of poetry and literature, an avid angler, a Christian. He’s a faithful husband, devoted father, doting grandfather. But to me, in my most clarion memories, he’s a hunter. And as any lover of poetry who hunts ought to be, a wingshooter.

For nearly two decades, he duck hunted nearly every day of the season. The rivers, sloughs, swamps and timber stands of Tallahatchie County were not yet commercialized. Duck hunting was not yet ”big business.” There were no million-dollar duck holes featuring various amenities. There were no side-by-side ATVs capable of driving you out to your blind. Duck hunting was tortuous, wading hundreds of yards through flooded fields and brakes, slogging through knee-deep mud. As there was no “technology” woven into clothing, hypothermia and frostbite were common threats.

Often they had to drag homemade, single-man drift boats down train-track right-of-ways to find where the water began before they could embark. It was tough, hard work. And the men who braved it back then were tough, hard men, wearing mostly long-johns, heavy sweaters and pants, un-insulated canvas waders. Out among the bitterly cold swamps and backwaters, away from their wives and civil society, many of them cursed, they drank bourbon or Schnapps to keep warm.

Once, while my father and uncle dragged a boat through a frozen lake breaking the ice with their boots and the butts of their shotguns their best friend, John Avant, sat shivering in the boat. In danger of hypothermia, he poured the fluid out of his zippo lighter onto his hat and burned it right there in the hull.

And so it was, when I think of my young life, as a of boy 7 years, I had yet to consider how grave a thing it was to beg my father to go duck hunting.

His answer was a quick, curt, “No.”

“But please,” I begged. “I want to go.”

“Absolutely not,” he said, “It’s too cold and you are too young. It’s not a place for a child.”

But then, miracle of miracles, my mother interceded, “Oh, Bud, let him go with you. It’s all he talks about.”

“Fine,” he relented. “But you set your own alarm. Get up and get dressed. We need to leave here at five. I’ll have breakfast ready at 4:30. Son, it’s going to be cold. Dress for it. Warm clothes. Warm socks.”

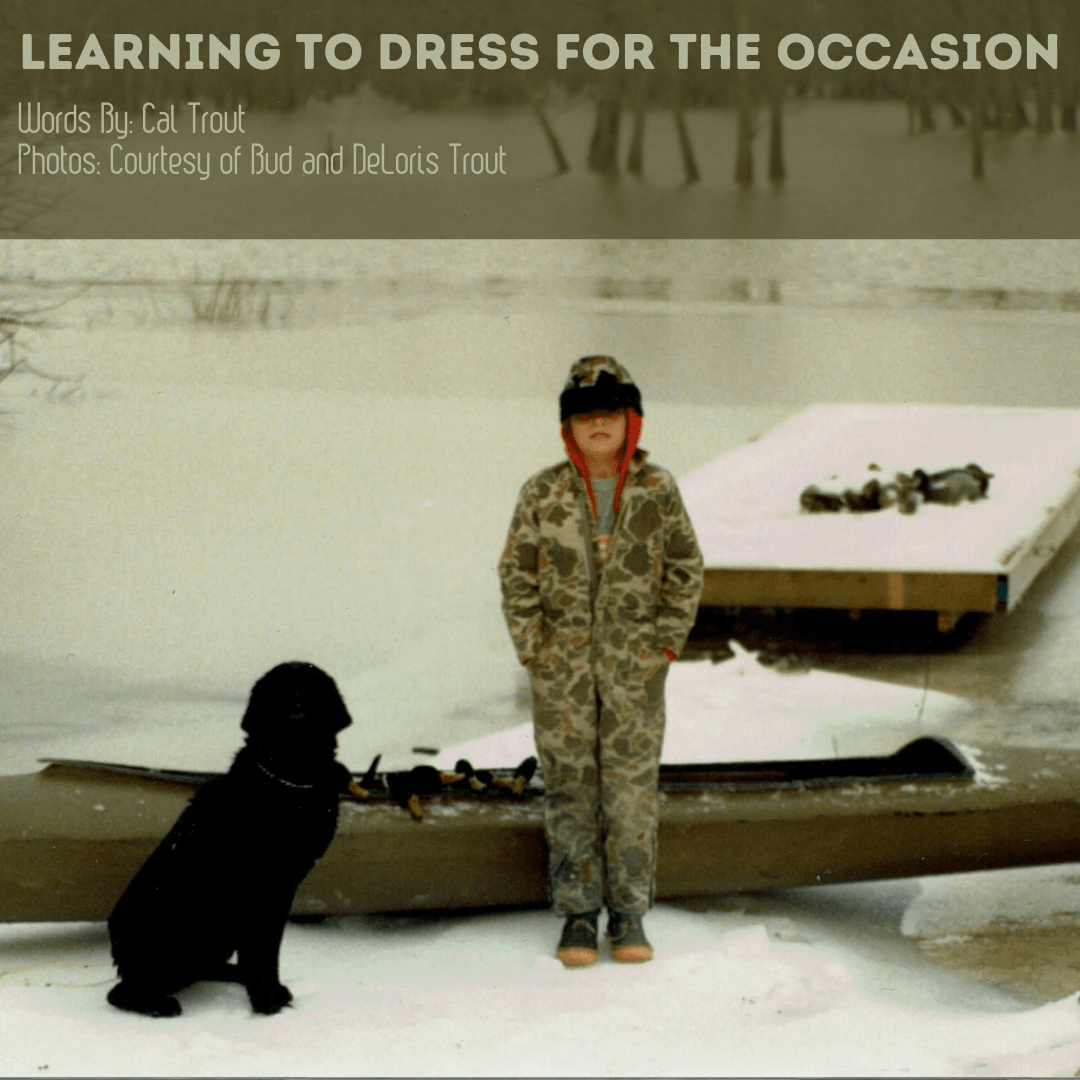

I could hardly sleep that night. The twenty-third of December, it might as well have been Christmas Eve. When the alarm rang the next morning I sprang to life. I got up, dressed in a pair of cotton long-johns, a pair of thin jeans, and a red Ole Miss hoodie. Out in the den waited my camouflage-printed overalls. My single-shot .410. I had on one pair of cotton socks under green un-insulated rubber boots. The high that day would barely reach the mid-30s. Pre-dawn temps: low 20s.

I vividly recall walking out of my room and seeing him dressing in the low and glowing light of a single lamp. A fire roared in the fireplace. All of his gear laid out on the couch next to my modest fowling piece and inadequate overalls. I could smell hot chocolate from the kitchen. It was my first glimpse into a world that was, in that time and place, uniquely masculine. I was ecstatic to enter a world occupied by my father and other men like him who were said to be ”mad at ducks.” A world wholly apart from attentive mothers and older sisters, who sheltered us and kept us from danger. Beyond excited, I bounded into the den and announced I was ready.

He took one look at me and said, “Son, you don’t have enough clothes on. You need to go back and put on the heavier pants and the sweater I put out for you.”

“I’m fine in this,” I offered, not wanting to seem green or lacking toughness. “I’ve got my overalls there. Plus, I’m hot already.”

“I’m sure you are,” he turned towards me, “but the heat is on and there’s a fire in the fireplace. Remember what I said last night, you can always take clothes off if it gets warm. You can’t put on clothes you don’t have.”

* * * * * * *

Earlier that year my parents gave me a pellet gun. While out in the backyard teaching me how to shoot for the first time, he taught me which eye was dominant and what that meant, how to hold a gun when shooting a rifle and how to put my cheek down on the stock to line up the sights. I’m right-eye dominant, so I was mounting the gun on my right shoulder. For some reason I kept taking my head all the way across the stock so I could look down the barrel with my left eye.

“Look down the barrel with your other eye,” he said gently. I held steady with my left. “Son, that’s not right. You’ll never hit what you’re aiming at. Look down the sights with your right eye.” I lifted my head, readjusted, then brought my head across and looked down it with my left eye. This exchanged repeated a half-dozen times.

Finally, he took the gun from me, modeled the correct form and explained it again. He handed it back to me, whereupon I did it the same way I had, with my left eye. Losing patience he said, “You can’t have your face all the way across the stock for a lot of reasons. If you’re going to learn it, you have to learn it correctly. That’s not how you shoot a rifle.”

I lifted my head, looked at him and said coolly, “This is how I shoot a rifle.” Then put my head back down across the stock, lined everything up with my left eye and pulled the trigger.

To this day, I don’t know where that BB went, but it was not into the can at which I aimed.

* * * * * * *

So on this morning of my first duck hunt, with all the excitement a young boy feels on his first real outing with his father, we came to loggerheads over, of all things, fashion. When I insisted again that I had my overalls and I would be fine, he demanded, “Go back and put on more clothes. Did you put on the wool socks? It’s been snowing. It’s bitterly cold. How you are dressed is not how you dress when you go duck hunting.”

I looked at him determined and said coolly, “This is how I dress when I go duck hunting.”

He turned, picked up his Browning, hung his brace of McCann duck calls around his neck, grabbed the thermos and said, “Okay. Let’s go.”

Stepping out of the truck onto the cold, frozen, snow-laden ground that morning I’d never seen a world sopainfully beautiful. We were on the banks of Grassy Lake between the hamlet of Tippo, Mississippi and the Tallahatchie River. Large hardwoods parted to reveal a small dock surrounded by frozen water. Cypress knees punctuated the lake. Large crystalline icicles clung to cypress boughs in trees that seemed old as time.

And, friends, I was cold. I don’t mean chilly. I don’t mean the air was a little brisk. That day holds fast as one of the coldest of my life. It was humid and in the mid-20s, with a 10-mph north wind. In the 15 minutes it took him to ready gear and unload the boat while I held fast to our lab, Belle, my feet were numb to the bone. By the time we paddled out to the blind I was utterly and immutably miserable.

While we didn’t stay long, we did stay long enough for the lesson to stick. It was a seminal day in my life. It is the day my father began teaching me how to be a man. Had it been an actual rite of passage, I, no doubt, would have failed. I remember complaining and feeling loathsome about needing to. I remember him looking down expectantly when I first said, “Daddy, I’m cold.” I recall an excitement like none I’ve ever known when the first flight of ducks came in.

Mostly, I remember feeling ashamed I was the reason we had to leave. But in his hunting journal all it says for December 24, 1986 is: “First serious hunt with Cal. He had an easy shot for his .410 shotgun. Got so excited he punched the button and breached the gun instead of pulling the hammer back. Second hunt for Belle. She made good retrieves, but balked a little going.”

I’ll trust his words at the time. Still, I’m not sure it was the excitement so much as it was the fact that I couldn’t really feel my thumb. But, the best lessons we learn are the ones that come with some price. I’ve never underdressed for a hunt since.

Nowadays, I operate a modest quail hunting preserve. This year I had the honor of taking a man on his first quail hunt. A dog lover, he was alone and as excited as a child of seven on the eve of his first hunt. It had rained a lot in the preceding days, and even though it was January, it was a sunny 68 degrees with highs predicted around 80.

As I readied the dogs, he prepared. When he stepped from around the truck his was wearing Thinsulate, neoprene chest waders and a heavy duck-hunting coat. I asked, “Is that what you’re wearing?”

“Yes,” he said, “I know it’s been raining. I don’t want my feet to get wet.”

I said, “I understand, but we won’t be hunting quail in chest deep water. Plus, it’s hot. Do you have regular boots?”

“Yes,” he cocked his head curiously, “But I don’t want to get wet.”

“I assure you,” I continued, “if you wear that, your feet will be soaked. We don’t wear chest waders to quail hunt.”

He set his jaw and said, “This is what I am wearing.”

Suddenly, I saw myself as my father must have all the way back in 1986. As he must have been, I was filled with frustration and, yes, sympathy for the coming lesson as I opened the dog box, hit the whistle and said, “Okay. Let’s go.”